I’ve found that if I don’t intentionally set aside time to be a full break from work, I won’t take it. Not only will I not take it, but sometimes it actually feels difficult to allow myself to relax. Instead, I’ll feel like I finally have time to work on research and writing, so I should make the most of it! And I have so many projects to finish that have been waiting for my attention! And I want to prep for fall so it’s not so stressful! It’s easy to think about how to fill up (and actually overfill) the coming weeks and months. And also: I know that this is the wrong decision.

Here’s what I do instead: I map out the weeks of the summer so I can see where my time is going. It’s the same basic process I use for the semesters, but the main focus is on protecting time when I won’t work. And again, this is harder to do than I’d like!! When I have to work on a paper revision, or I finally have time to meet with collaborators, I don’t want to say no to anything. But the truth is, I’ve not been taking substantial breaks from work since starting on the tenure track (...or more accurately, even before), and I FEEL it. This is the perfect recipe for burnout, especially coming off an academic year that had higher demands, stress, anxiety, and exhaustion than ever.

I am reminded when doing this sort of planning that if YOU don’t protect your time, no one else will.

Also: do you know what it feels like to not work for a full week or two… or even a month?! I mean, not checking email, not mentally organizing projects, not projecting into the future to address what’s coming up. Really taking time off is a challenge, in terms of the planning for it, the allowing yourself to actually do it, holding boundaries with people who might want things from you, and holding a boundary with yourself to not slip back into working during these times. For me, this is the hardest part: I’m pretty good at knowing on the calendar when I should be able to take time off, but then letting myself do it feels so much harder than I think it should.

Given how stressful this past year has been, it is more critical than ever to make and protect time to recharge and rest. Here’s how I’m doing this:

Making a list of all the projects that I NEED to get done or make progress on this summer

Protecting time in the first half of the summer to do that work and to get where I need to with those projects (and teaching a summer class!)

Working during May and June KNOWING that I will take time off in July and part of August.

Prioritizing the most important projects and accepting that the other stuff will have to wait until fall (this is deeply uncomfortable, btw!)

Marking dates on my calendar for travel with family (1 week in June, and 1-2 weeks in August), for family visiting us (1 week in June, and 1 week in July), and then ALSO carving out at least a week in July where I know I will be completely away from work and will do things that feel fun/restful

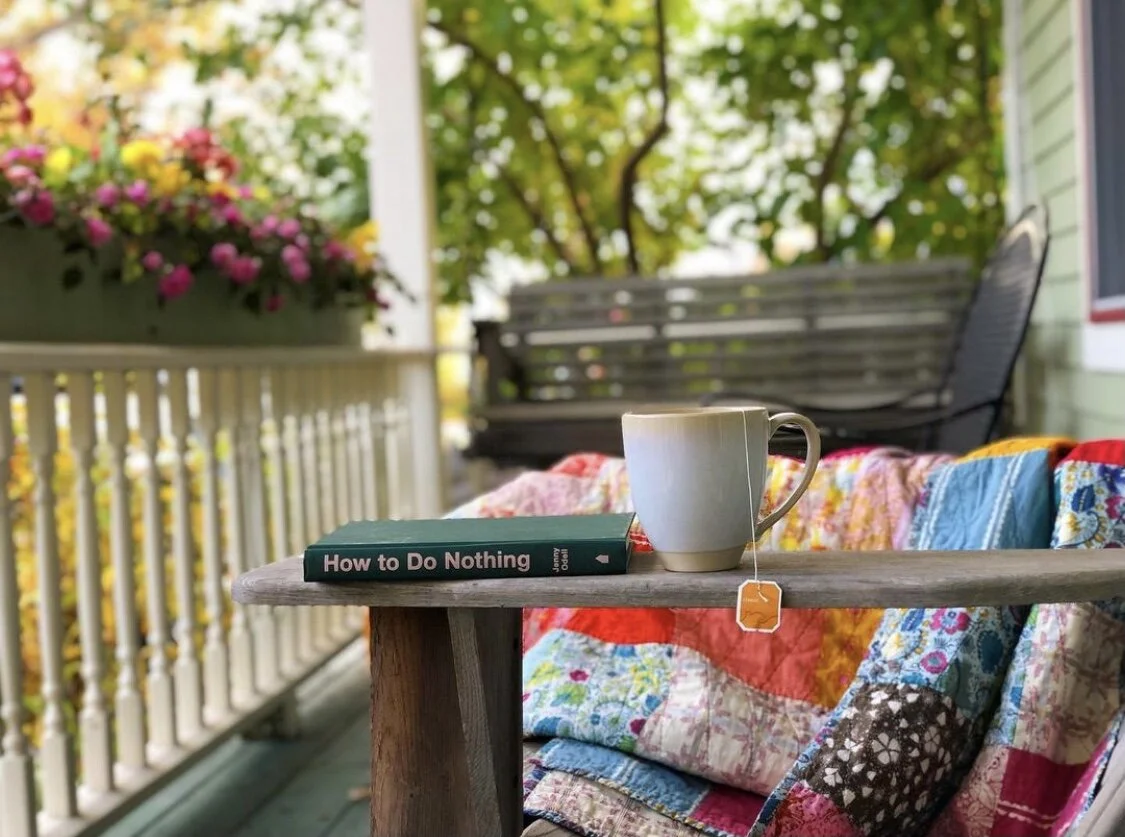

Part of this plan also requires me to have a sense of what I’m doing with my time off, otherwise it also tends to feel overwhelming. To do this, I have a list of what I want to do for pure enjoyment-- not out of obligation or duty. For me, this list looks like reading books for fun, going on long walks or hikes, baking, quilting, and watching fun tv shows.

What I’ve noticed in the past is that the first couple of days of taking a break look like mostly catching up on rest (naps, moving slowly, not trying to do too much!), and then the next couple days I have more energy for fun projects (though to be fair, I often get sucked into organizing or cleaning parts of the house!).

One thing that I want to note is that this often feels deeply uncomfortable. Academic culture does not value or support this approach, and I feel this physically in my body when I try to really take time off. I remind myself that the discomfort is ok; it’s a good thing to sit with because it confirms how deeply entrenched I am in my work and how deeply I need the break from it.

And here’s the (ironic) thing that is so critical for me to remember: it’s when I get into this groove of doing other non-work enjoyable activities that I start to get the BEST work ideas; frameworks for papers, connections between research ideas, easier ways to do things, they start to emerge! In fact, it can become tricky to not give myself over into work time when this happens; if I have a great idea I can’t pass by, I’ll give myself a short sprint of work time (30-40 min) to do a brain dump and catch everything I can about the ideas, and I’ll leave them to marinate for later. My best/most inspired work nearly always starts this way.

The thing to remember is to clear the space so that there’s room for the good stuff to rise up to the surface; it’s clear that this doesn’t happen for me in the midst of the semester when I’m feeling buried under email and meetings and obligations. And it’s not ok to wait to take breaks, because once Fall rolls around again, the train has left the station for another year out there on the rails-- hanging on until the next break.